Buíque e Inajar (PE) - Alcione Albanesi, 57, had gathered her four children in São Paulo to share some important news with them. "They thought I was pregnant again," she said, laughing.

She announced, indeed, that the family would grow much larger. From that moment she would spend half of each month in Brazil's northeastern backwoods to dedicate herself to the thousands of people served by the NGO she founded in 1993, the Friends of Good.

"They even signed a little contract that they were aware that Mom has another family and would take care of it until the end of her life," she recalled.

Until then, Alcione had been visiting this other "son" once a year. She started visiting once she learned about the misery in the world's most populous semiarid land—Brazil's Northeast. A successful businesswoman, she began a philanthropic mission by gathering a group of friends to distribute food and clothing in the Northeast at Christmas.

"I read, I heard, but it changes everything when you're there, in the midst of that abandonment. It was a total transformation within me," she said of the impact of the first trip. She repeated this religiously for ten years, traversing villages where children did not know Santa Claus.

The decision to move from being the female version of Bom Velhinho to acting in a more structured manner - the moment of the "contract" with her family - came in 2001.

Since then, the NGO has won new projects and spread to 130 small towns in Alagoas, Ceará, and Pernambuco.

Under the leadership of Alcione, the NGO opened chestnut processing factories, created cashew plantations, launched sewing and craft workshops, opened schools and even created small towns, the so-called Cities of Goodness.

Alcione changed the direction of her work when she met a mother suffering from elephantiasis.

"Dona Geralda arrived with bleeding legs, and I took her home. She gave me the recipe for ending hunger: I put a lot of water with a small amount of beans to feed the children," Alcione said. "That stayed inside me. We couldn't just go through their lives anymore."

The businesswoman refutes the critics of welfare who repeat the maxim that "it is necessary to teach how to fish, not to give fish". "In dryland, one does not fish," she argues. "There is no work there. They live by planting and losing. There is no way to reverse it without human intervention."

But it was also necessary to go beyond philanthropy. And so she inaugurated the first City of Good in Catimbau, district of Buíque (PE), located on a farm acquired by Alcione and friends. Her organization planted more than 100,000 cashew trees, the raw material that feeds the nut and candy factory, generating over 300 jobs in the region.

Some of the workers live in brick houses inside the village, which has a square, museum and sewing workshop. "We get people out of mud houses, but it's no good if we don't offer education and work."

Sales of the premium nuts to large retail chains in the Southeast already cover 30% of NGO costs. The goal is to reach 50% in three years, in a model that seeks to be self-sustaining.

In the vicinity of the factory is the Transformation Center, a space of 3,000 m2 with extracurricular and vocational courses for children and adolescents. In all, 10,000 children already benefit from the NGO's educational programs.

"By the end of the year, 300 young people who have gone through Amigos do Bem will have entered college. They are children of illiterate parents, who ran in the dry woods and now sports diplomas, breaking a cycle of misery and exclusion."

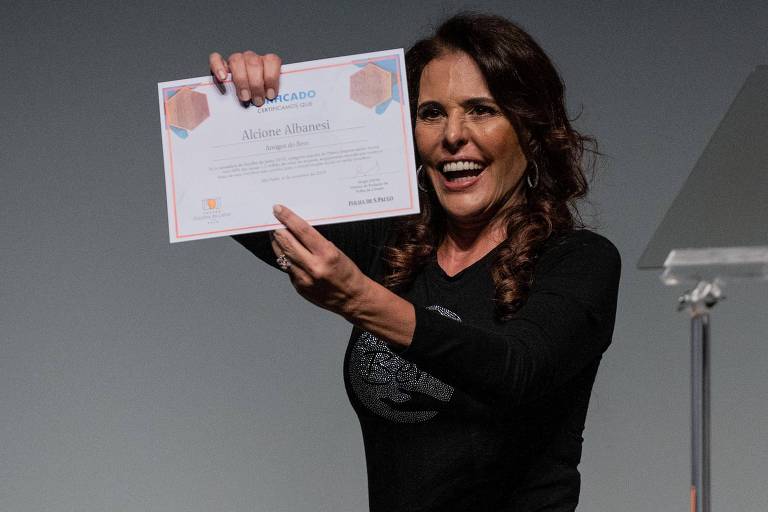

Celebrity in the Backlands

Alcione is a celebrity in the backlands. During Folha's visit to Pernambuco, she arrived at the transformation center honking her truck. A crowd of children hugged her and greeted with her placards of thanks.

She was almost speechless, but that didn't stop her from communicating with the help of her husband and one of her daughters, Caroline.

"I love you!"; "I'm proud of you!" She whispered from the stage.

Amid the melee, she asked about the sick son of one, the grandson of another. "I have 75,000 children," she said.

Alcione's greatest source of inspiration is her mother, Guiomar, who founded 11 nurseries in São Paulo. As a child, I spent the holidays taking care of children and insisted on going to Ceasa to collect fruits and vegetables. "I would sit on the crates and not leave until the marketer donated," she recalls.

A model in her adolescence, Alcione really wanted to open a sweets shop. At 17, she had a clothing business with 80 employees.

Ten years later, she ventured into buying a hardware store on Santa Iphigenia Street — where, at five-foot-eight inches, she was harassed and underestimated by other shopkeepers, all men.

The company grew to become in 1992, FLC, a company that dominated 35% of the Brazilian hardware market, until then dominated by multinationals like Philips.

Alcione remembers fondly the 71 trips she made to China when she saw the opportunity to import foreign goods during the Collor administration.

She landed without knowing anyone or speaking Chinese. She searched for suppliers on the Yellow Pages with help from hotel staff.

She filled containers with lamps, but she found that the product was not compatible in Brazil. She did not give up. She scheduled the next trip and had 13 factories in the Asian country as sole suppliers.

In 2014, she made "the hardest and most conscious decision" of her life: she sold FLC to devote herself to Friends of Good.

For her, the NGO, which has gained a social impact business arm, is more complex as it operates in various fields, from drilling wells to training professionals.

"We make the complete cycle of life: from the first baby clothes to the opportunity for employment in adulthood. This is hard."

Alcione speaks a lot about God. "I don't wake up without praying." Also, when she wakes up, she repeats to herself, "It's going to be all right." "I don't allow myself to lose confidence."

She sleeps five hours a night, and has an "unbearable disposition," jokes her husband, businessman Ricardo Yolle, 44. "But more than willing, she has a knack for awakening that people want to be better," she said.

Alceu Caldeira, 52, a former FLC director, accompanied Alcione when she left the company and became her right-hand man at Amigos do Bem. "She's picky, but she's got a lot of feeling."

Alcione plans to work in the backlands until the last day of her life and she plans for her children to be her successors. "With technology may come growth, but the foundation, love, will never be lost," she said. "The transformation the world needs happens from the inside out."

Translated by Kiratiana Freelon