Latest Photo Galleries

Brazilian Markets

12h03 Bovespa |

-0,14% | 129.028 |

16h43 Gold |

0,00% | 117 |

12h17 Dollar |

+0,39% | 5,0873 |

16h30 Euro |

+0,49% | 2,65250 |

ADVERTISING

Yaripo, the Yanomami Antenna to the World

09/12/2017 - 14h55

Advertising

MARCELO LEITE

SPECIAL ENVOY TO PICO DA NEBLINA

The Yanomami man is, above all, a lord. He is gentle and careful with the guests of the recently launched Yaripo Project, which promises to reopen ascents to Pico da Neblina (Fog Peak, in Portuguese), but proud and distant. Almost unreachable, like the mountain.

Whoever thinks they are inferior-or fierce, like the controversial American anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon-now has a chance to change their minds by climbing the highest mountain in Brazil in their company. There is already a waiting list for 2018 and 2019, subject to some trail improvements.

| Marcos Amend/Folhapress | ||

|

||

| Vegetation encountered on the path |

A warning to potential hikers: the hostile environment does not lend itself to expeditions. The dense forests typical of the Amazon have wet soils crisscrossed by slippery roots, mud pits, loose stones, and lots of seasonal rivers. It is rainy and hot.

Annual precipitation can exceed 3200 mm in the nearby city of São Gabriel da Cachoeira (AM), which has an average air temperature of 26 degrees Celsius (79 degrees Farenheit).

Physically and psychologically, it is not an easy hike. But with some preparation, any adventurous tourist can meet the challenge. And the pay-off is enormous: nothing compares to reaching the summit.

| Marcos Amend/Folhapress | ||

|

||

| It's a 70 kilometer hike to the top and the overall elevation is 4,400 meters |

But without the help of the Yanomami, don't even think about it.

"Yaripo," in the Yanomami language spoken around Maturacá (AM), is "Mountain of Wind." In spite of the name, the group of 11 visitors in which Folha participated summited on July 21 under calm winds and a warm sun, with a temperature of 21 degrees Celsius at an altitude of 2995 meters (9826 feet).

The fog came and went. It was possible to see the neighboring peak named March 31 (2974 meters, or 9757 feet), the second tallest mountain in the country, and the Venezuelan plain spreading out from the foot of the sheer cliff.

The access trail is on the Brazilian side, which follows several impressive views of the Imeri Range. It is 36 km (22 miles) on foot, with a total elevation gain of 2900 meters (9514 feet) in five days.

| Marcos Amend/Folhapress | ||

|

||

| Members of the group resting between camping sites |

The full 72 km (44 miles) course takes eight days to complete. It occurs entirely within Yanomami Indigenous Land, which has a total area of 96,700 km2 (larger than Portugal), of which 11,300 km2 is superimposed with the Fog Peak National Park (with an area of 22,500 km2, it is a slightly larger than the state of New Jersey).

Since 2003, however, the trail has been officially closed. The Yanomami of the region decided they would no longer tolerate the invasion of their lands by groups organized by tourist agencies, which went to Pico da Neblina without authorization from FUNAI or ICMBio, Brazilian federal agencies responsible for indigenous lands and conservation areas, respectively.

Despite this, the excursions continued to take place, almost always with the participation of Yanomami from the villages of Maturacá and Ariabu, which have a combined population of about 1,700 people. As porters and guides, they earned a pittance.

| Marcos Amend/Folhapress | ||

|

||

| Picture taken by a drone portrays the 11-person team, which Folha was part of, that hiked to the top of the Pico da Neblina (Fog Peak) |

DESIRE

Pico da Neblina is at the top of list for adventurous tourists and climbers like Silvio Alpendre, who is now 57 years old. In October of 2016 he and two friends thought they were in good hands when they received an invitation to summit with a retired Amazonian Military Police colonel, who claimed that he had arranged everything with the Yanomami.

"In fact, it later became clear that what he organized was a kind of invasion," laments Alpendre.

When they arrived after dark in Maturacá, armed soldiers from the 5th Frontier Battalion of the Brazilian Army confronted them with flashlights in the face: what were they doing there? The MP colonel informed them that they were going to climb Pico da Neblina and had arranged everything with Júlio Goes, a powerful Yanomami in Ariabu.

| Marcos Amend/Folhapress | ||

|

||

| The Pico da Neblina path includes a stretch with a haphazard bridge made out of tree trunks |

The next day, the group had not been on the trail for more than 40 minutes before a military official reached them with news that two boats full of Yanomami armed with rifles and clubs were coming after them. It would be most prudent to turn back.

Upon return to Maturacá, the group was informed that there would be a meeting the next morning to decide what would be done. When the tourists arrived at the gymnasium at the neighboring Salesian mission, they were put in chairs in front of wall-to-wall bleachers which gradually filled while local leaders inveighed against them in Portuguese and in their own languages.

In the end, the Yanomami voted that the group would be allowed to return to São Gabriel da Cachoeira. The result of this interrupted excursion was the loss of several thousands reais spent on airplane tickets, hotels, and cash paid to the colonel for food and porters.

Upon hearing that the retired colonel thought that the ordeal was worth the "experience," Alpendre says that he "only learned what not to do." Despite the embarrassment, he reports that he did not feel physically threatened at any time.

This group could not have chosen a more inappropriate time to risk entering indigenous land without permission. The Yaripo Ecotourism Project was in a crucial period after three years of hard work, with several training courses and meetings involving FUNAI, ICMBio, and AYRCA (The Yanomami Association of Rio Cauaburis and Tributaries).

| Marcos Amend/Folhapress | ||

|

||

| A member of the Yanomami tribe carries a basket/backpack; the containers that are made from vines can weigh up to 35 kilos |

Much more than merely ill-informed strangers, the colonel's group intruded upon an otherwise great moment in which, AYRCA at last had finalized the Visitation Plan required by ICMBio's standards for national parks.

RADIO

Luiz Capovila breathed a sigh of relief when the Motorola radio he carried crackled with the voice of Salomão Mendonça Ramos, AYRCA coordinator of the Yaripo project, speaking from Maturacá. It was the fourth day of expedition, when the group had already left behind the dense forest and entered a sea of bromeliads, near the base camp at 2000 meters altitude (6560 feet). Ahead lay the majestic panorama of the Montila Range.

"This took a 37 kg weight off my shoulders," said the 29-year-old Sao Paulo engineer, who had spent the three previous days worried by the radio silence. This was just a figure of speech; the hardened adventurer continued carrying his backpack full of equipment, spare flashlights, a machete and a satellite phone.

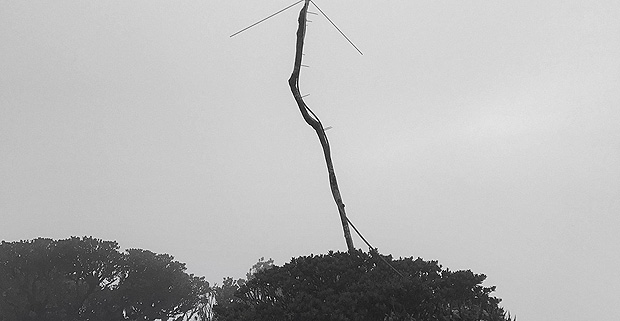

Capovila was tasked with testing a provisional VHF radio system to keep the group in communication with the village while on the trail. Only 48 hours before the Yaripo trek, he had returned from another strenuous three-day journey to install a repeater antenna atop the mountain range that interrupted the radio signal between the trail and the village.

| Marcos Amend/Folhapress | ||

|

||

| Pico da Neblina, the highest mountain in Brazil, located in the state of Amazonas |

In addition to collecting the temporary equipment used in the test, which required a third expedition of the engineer within a two week period, he will have to return in November to install a 10-meter antenna in the correct location. This will require some construction work, which will be difficult to perform without helicopter support.

The plan is to take paying tourists to Pico da Neblina in 2018 or 2019, and the radio system cannot fail.

This second AYRCA expedition, in which the Folha took part, had a more technical purpose. In addition to Capovila, it mobilized Nelson Brügger of the Brazilian Confederation of Mountaineering and Climbing with the mission to evaluate the more difficult trail segments, which includes steep rock walls that today can only be climbed with a series of ropes. Brügger is planning the installation of 58 metal rungs to replace the ropes.

The guide Tomé Fonseca, 42, led the group of 13 Yanomami, each carrying a jamanxim (a basket-backpack woven of vines) weighing up to 35 kg. The other 12 guys in their 20s and 30s, who speak little and walk a lot, were always willing to take on more weight to relieve the visitors who were unaccustomed to the environment. Several carried a pëë (pronounced "pey-hey"), a small roll of tobacco mixed with cotton and ashes between their lower lip and gums, which is a near universal habit amongst Yanomami men.

| Marcos Amend/Folhapress | ||

|

||

| Repeater antenna installed on the top of one of the mountains en route to the peak |

The group included representatives from ICMBio, Luciana Uehara, and from FUNAI, Anderson Vasconcelos and Alexandre Viana. From the Instituto Socioambiental (ISA), which provides consulting services to the Yaripo project, was Lucas Lima, a geographer with a master's in anthropology (and he is a master, truly, in giving organizational advice to the Yanomami without condescension).

The expedition was funded at the initiative of professor Julie Michelle Klinger of the Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies at Boston University, who brought her student, Bridget Marie Baker and her colleague, José Renato Peneluppi, Jr. Folha'sreporting team, which paid its own expenses, included the ecotourism consultant and photographer Marcos Amend.

QUARTZITE

The expression "sea of bromeliads" is metaphorical, but it has some connection to reality. There is a lot of water beneath the botanical mass. Both accumulate over a layer of impermeable rock to create the mud pits that many in the group elected as the worst part of the trail. Some of the sparse trees have aerial roots to secure themselves on the unreliable ground; together with the dark mud, it is reminiscent of coastal mangroves.

| Marcos Amend/Folhapress | ||

|

||

| It's a 70 kilometer hike to the top and the overall elevation is 4,400 meters |

After this variety of marshland, the trail fills with lots of loose stones, some pinkish in appearance (quartzite). Here and there appear large conglomerates, which is a type of sedimentary rock composed of an infinite number of aggregated round pebbles, a sign that they spent a lot of time submerged and moving along river bottoms perhaps billions of years ago.

They came to a stop there at a height of more than 2000 meters because Earth's crust rose in the region some 65 million years ago and formed the Imeri mountain range, one of many "inselbergs," (literally, island-mountains) rising from the Guiana shield.

The Yanomami have been around the area for a long time. They go as guides and porters for clandestine tourists, from which they earn a third of the payment listed in the Visitation Plan submitted to ICMBio (at least R$ 1000, approximately US$ 350). Or they accompany researchers seeking new bird, reptile, or insect species. Others carry equipment for illegal gold-diggers in the mountains -that is, when the natives themselves are not operating the machinery and excavating ravines.

They also revere Yaripo because there are many "spirits" there. There are some that see the spirits as prohibiting women from reaching the peak, a vision fought against by Kumirayoma, the women's association of Maturacá and Ariabu. Maria de Jesus Yanomami, one of the members of the previous expedition, was the first Yanomami woman to summit Pico da Neblina.

Women or men who venture on the trail will have to deal with the lack of privacy. There are no bathrooms, only some vegetation to hide those taking a squat. The clearings opened for the camps are small, and the sleeping hammocks are hung centimeters apart beneath a 7 m x 4 m tarp that doubles as a roof. The tarps are green so the tourist camps are not confused with gold-diggers, who use yellow tarps. The Yanomami sleep in smaller tents right next door.

| Marcos Amend/Folhapress | ||

|

||

| Tourists use green tarps in order to stand apart from the gold miners, whose tarps are yellow |

The kitchen is an open fire. The table, a piece of folded tarp placed on the ground, or the leaves of some relative of the banana tree (these can also be used to wrap food that is roasted directly in the coals, the Yanomami cooking technique called "haro-haro").

The basis of the menu -only one full meal daily, and the end of the day's hike- consists of manioc flour with rice and beans. The porters refuse to serve something other than beans, even though it requires carrying a 12-liter pressure cooker up and down the mountain. Animal protein varies between salted beef, smoked sausage, and fried chicken, which tend to run short on the way back. Saltine crackers, northeastern-style couscous, and the occasional tapioca accompanied the morning coffee.

GENDER

The discomfort and exhaustion of the last leg (3300 feet elevation gain in four hours) are forgotten as soon as the summit is reached. After four days of looking at the ground, measuring each step on the rugged terrain, the reward is a grand panorama of cliffs unfolding beneath the peak, atop which lies a mast bearing the Brazilian flag that has toppled in the wind.

Even as the fog intermittently encloses the peak, the vast Amazonian plain seen from this mountain in the clouds fills the eyes with light, green, and tears. The Venezuelan side of Yaripo is almost vertical, an abyss that left all astonished and aware of their own smallness.

| Marcos Amend/Folhapress | ||

|

||

| A Yanomami community near the top of the Pico da Neblina (Fog Peak) |

Julie Klinger of Boston University pulls out a satellite phone and calls her husband with whom she talks excitedly about the conquest. When finished, she offers everyone the opportunity to contact their loved ones, and many accepted the generosity.

Celebratory rounds of water, chocolate, and "paçoca" (manioc flour mixed with dried beef) commemorated the ascent. Hugs multiplied around the group, as did photos and nods to the camera drone flying overhead (probably the first drone take-off from Pico da Neblina).

There were three "napëpe" women, but only two -Klinger and Luciana Uehara- completed the final ascent. Not a single woman was integrated into the Yanomami contingent during this second expedition, an absence that was addressed in the assembly to elect new AYRCA leadership two days after the group returned to Maturacá.

Invited to sit at the assembly table and compelled by the directors of Kumirayoma to speak about the importance of women's participation in the expedition, Klinger outlined several reasons why equal participation is important. First, she stated that she was only there because she decided to support the expedition after seeing a video about the pioneering expedition of Maria de Jesus to the summit, which was recorded by Marcos Wesley Oliveira of the Instituto Socioambiental. The participation of women would also make it easier to obtain funds to support subsequent expeditions.

The Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies at Boston University, explained the professor, is guided by UN guidelines that consider gender equality inseparable from the concept of sustainable development, that is, the active participation of women. "Not only as cooks, but as porters and even guides," she pointed out.

| Marcos Amend/Folhapress | ||

|

||

| Stretch of the BR-307 highway, where automobiles typically get stuck |

In addition to this, women from the local community would make female tourists more comfortable in situations involving health and hygiene (such as checking each other's body parts for ticks). Finally, without the guarantee of equal opportunity for the Yanomami regardless of gender -as envisioned in their own Visitation Plan agreed to by all the communities, ICMBio and FUNAI- American support for future expeditions could be threatened.

The usual argument made by Yanomami men that women could not handle carryingjamanxins up the mountain infuriates the village women, who routinely carry baskets loaded with up to 50 kg of manioc or fire wood from their fields to their homes. In reality, what is actually at stake is the distribution of revenue, which men prefer to keep to a small group of relatives and political allies. Opening jobs to women would increase the number of people in the pay rotation.

The Yanomami man is, despite everything, a lord -very aware of the tradition in which lords and ladies, waro and suwe, occupy different spaces in society.

There is no place for the women, for example, in snorting paricá, a kind of powder that allows the pata (elders) to go to a different world and communicate with the spirits that inhabit Yaripo, negotiating with them to ensure the well-being of the napëpe who venture onto its slopes-a "pajelança", shaman ceremony that moved the foreign visitors very much.