In June 2020, Black Lives Matter protesters tore down the statue of Edward Colston, a 17th-century slave trader, and threw it into the waters of Bristol Harbour. Images from the episode went around the world. A month earlier, George Floyd had been murdered by a white police officer in Minneapolis, triggering a worldwide wave of protests against racism and violence by law enforcement officials.

The Bristol event gave rise to much discussion of historical revisionism. Colston trafficked over 100,000 Africans to the Caribbean and the Americas. He was a philanthropist who poured a lot of money into his city, hence the statue, but who branded the chests of women and children with his company's initials, hence the outrage. The explicit cancellation has also made many organizations review their own archives, worried about troublesome pasts.

One such company was the English newspaper The Guardian. Its founder, John Edward Taylor, was a Manchester cotton merchant who, with the support of fellow businessmen, created, in 1821, The Manchester Guardian. The fund that today runs the newspaper, one of the most important on the planet, commissioned researchers and historians to investigate investors' resources. The first results were known last March: Taylor and at least 9 of his 11 partners had connections with slavery.

The paper's ownership group issued an apology and announced a decade-long restorative justice program focused on communities descended from those affected in the Caribbean and the US, investment in scholarly research on transatlantic slavery, and several editorial actions. You can follow the project on the Guardian website, which publishes a series on the subject, "Cotton Capital".

Evaluating the merits of the initiative is a complex task, which does not fit in this space. In strictly journalistic terms, however, it is a spectacular demonstration of transparency and, obviously, financial health. Few press vehicles reverberated the project.

It's not easy to stir up aspects of the past, even more so when it's recent and you're still working with human memories, not just with history books.

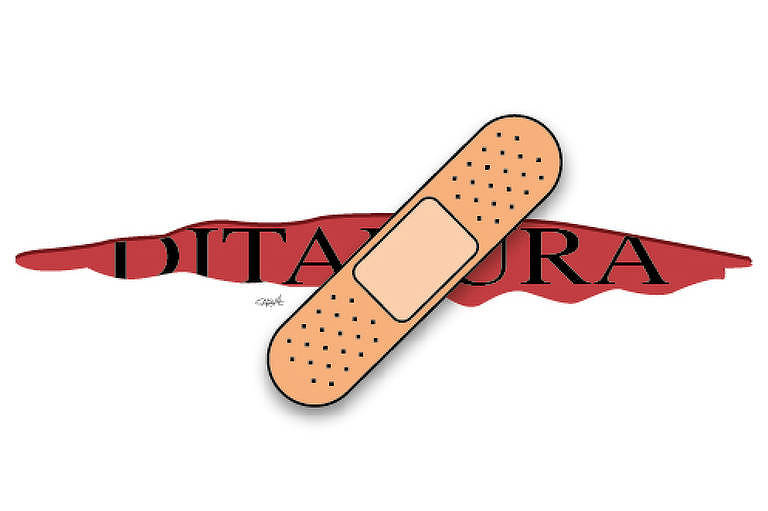

Folha made its own move last week. In a two-page publication in the Ilustríssima section, without headlines on the first page and no visibility on the homepage, it revealed an internal report produced in 2005: "Document addresses the trajectory of Grupo Folha during the period of the military dictatorship". Along with Fiat, Petrobras, Itaipu, and others, the newspaper is the only press vehicle in the country scrutinized by a Unifesp survey on the involvement of companies in the repression movement. The project is carried out funded by part of the compensation money paid by Volkswagen do Brasil after agreements with the Prosecution Service in 2020.

Volkswagen AG, besieged by a series of news articles in Germany, hired a historian to go through its own drawers. The check came later to the Brazilian branch. The story was recalled last week during the endless discussion about the automaker's advertisement that reunited Maria Rita and her mother Elis Regina, resurrected with the use of artificial intelligence. For the commercial's detractors, Elis and Belchior cannot sell those who sold themselves to the dictatorship.

It doesn't seem to be just a coincidence that the theme is in vogue. Two days after Folha's publication, the Agência Pública news agency aired a long reporting piece on the subject: "Documents indicate that Folha's alliance with the dictatorship was stronger than the newspaper admits to." The provocative parallelism between the titles is repeated in a certain way in the texts. Characters, facts, and testimonials are largely the same. What changes, and a lot, is the interpretation.

Agência Pública exposes Folha when reporting that it took them a week to get the requested other side. It also concludes that the newspaper, when publishing the internal report last Sunday (2), anticipated its position in response to a report that had not yet been published.

The report is from 2005. Its author, Oscar Pilagallo, published "História da Imprensa Paulista" ( History of São Paulo's Press) in 2011, where much of the initial research is reproduced. Equivalent content was made public in 2012, with the launch of "Folha Explains Folha", by Ana Estela de Sousa Pinto. In 2014, in an editorial, Folha recognized that it was wrong to support the dictatorship in the first half of its regime. In 2020, during the campaign to value democracy, then threatened by Bolsonarism, it reiterated its self-criticism. There was no lack of opportunities before last Sunday for the newspaper to make a timely and in-depth reflection on its role during the dictatorship. Perhaps even in an open debate with society, an institute so dear to the newspaper.

Transparency has to be an initiative, not a consequence of time, invariably relentless.

Translated by Cassy Dias