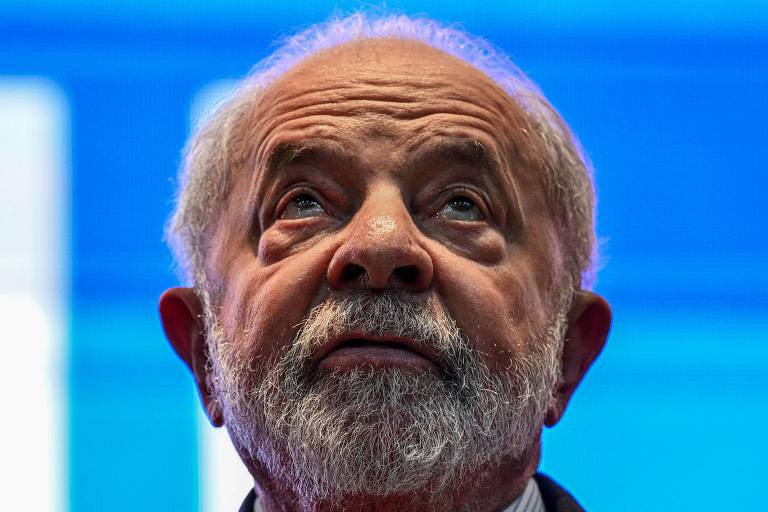

Given the political and institutional tensions that have increased in recent years, it will be particularly painful — and dangerous — for a new stage of economic regression to directly affect the well-being of Brazilian society. The government of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT), unfortunately, has made this risk higher.

The bet on state hypertrophy as a means of resolving conflicts and shortages, which since before taking office has translated into a continuous and unsustainable increase in public spending, makes it difficult to control inflation, lower interest rates, and, therefore, resume production growth and income on a long-lasting basis.

The new budget regulation, which is being discussed in Congress with the approval of physiological forces, only establishes weak limits to the increase in expenditure, without offering a reliable prospect of containing the public debt, which today is already at exaggerated levels for an emerging economy.

Judging from the view that lies ahead, either there will be a disproportionate squeeze in the tax burden or a new escalation of indebtedness. In both hypotheses, investment, and employment tend to get stifled.

One block of mediocrity would already be a misfortune for a country whose per capita income is still lower than ten years ago. There are further dangers, though.

Lula tries to promote a counter-reform of the advances abnegated by his party's ideologues. This is the case of the obsessive harassment regarding the Brazilian Central Bank's autonomy, which favored a change of government without major financial upheavals —in contrast, incidentally, with the explosion of the dollar and interest rates in 2002, with the PT member's first presidential victory.

Not satisfied with interrupting privatizations, the mandatary seeks to regain control of Eletrobras, sabotages the legislation that professionalized the management of state-owned companies and weakens the regulatory agencies.

With the same statist, corporatist, and clientelistic impetus, he invests against the legal framework for sanitation, instituted in an attempt to universalize a service to which around 100 million Brazilians shamefully still do not have access, a reflection of the state model that was in force for decades until 2020.

Subsidy policies for companies, which concentrate income and generate inefficiency, are revived under the pretext of strengthening the domestic industry. Encouraging the return of supposedly popular cars adds a tragicomic tone to the nostalgic agenda.

All things considered, however, economic excesses cannot obscure the return to institutional normality with Lula's election.

After four years of continuous threats to democracy under Jair Bolsonaro (PL), it is encouraging that the institutions have avoided a rupture, that the Armed Forces have respected their constitutional role, that the dialogue between the Powers has been re-established and that the president does not entice followers and the state apparatus against the criticism.

The sovereignty of the polls and the alternation of power end up working as an antidote against bad economic policies. Governments that impoverish the general population are not reappointed. Therein lies the tenuous hope that Lula will reverse the repetition of old mistakes —or, at least, that the National Congress, now more of a protagonist, will do so.

Translated by Cassy Dias