To travel the three miles of the Janelão trail, in the Peruaçu Caves National Park is equivalent to having a master class on the geological and archaeological past of Brazil. However, not many people take that class. In 2017, the park received only 6,200 tourists.

Located almost at the border of Minas Gerais with Bahia, at the threshold of the savanna-like cerrado and the semiarid vegetation of the caatinga, Peruaçu is off the beaten track. But it is worth every penny spent on the airfare to Montes Claros and the car rental to reach the towns of Januária, 400 miles from Belo Horizonte, and Itacarambi, next to the national park. Januária, 27 miles away from the park, offers the best lodging options.

A few miles after the park's entrance, along a somewhat maintained dirt road, is the beginning of Janelão trail. From then on, the visit continues by foot along 1.5 miles in a well-structured path, that would be considered easy if not its hundreds of steps. It takes five hours from start to finish, but there is so much to see that time seems to pass quickly.

One of the first sights is a high limestone wall that unveils a sequence of prehistoric drawings.

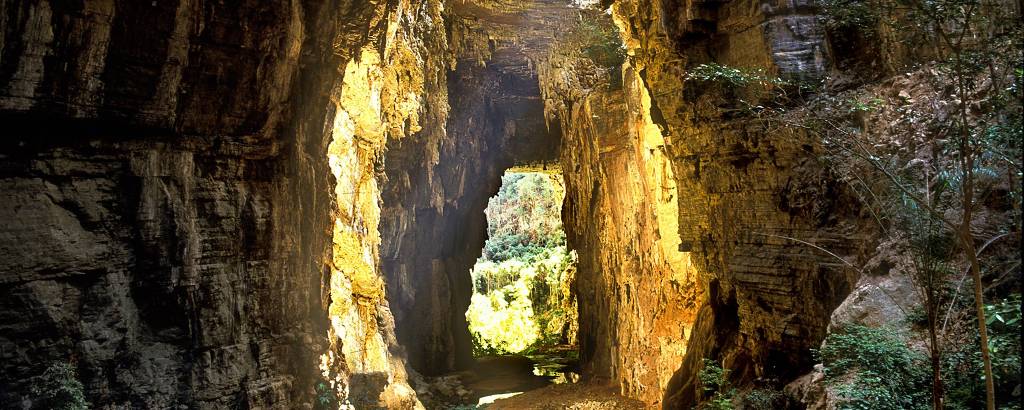

Up until that point, it's not clear why the trail is called Janelão (in English, Big Window), but a few hundred yards ahead, the mystery is over. After the first uphill, the hiker catches a breathtaking landscape featuring a sequence of passageways and skylights, all sculpted by the water in the whitish rock for hundreds of millions of years.

Two vertical slits in the cave's walls, between a hole in the cave ceiling, 330 feet above ground, show the so-called "Big Window." Sunlight shines in between the rock formations into the red dust ground, where the river Peruaçu runs.

The name Peruaçu means, in the indigenous language Tupi means "big hole." Nothing more appropriate to this place, with rock formations that geologists call karst, and that started to take shape between 542 million and 2.5 billion years ago.

Translated by NATASHA MADOV