Ingredients: 1 cup of warm milk; 3 eggs; 4 tablespoons of butter; 2 cups of sugar; 1 cup of chocolate powder; 2 cups of wheat flour; 1 spoon of baking powder.

How to make it: beat the ingredients well and bake until golden brown.

If we were in a dictatorship, this article, about censorship, would not be published. A censor would have vetoed it, and instead, the newspaper would have published the chocolate cake recipe.

Goodies and poetry would also fill this space if the text were critical of the president or an ally, or if it brought information about the pandemic that the government preferred to omit.

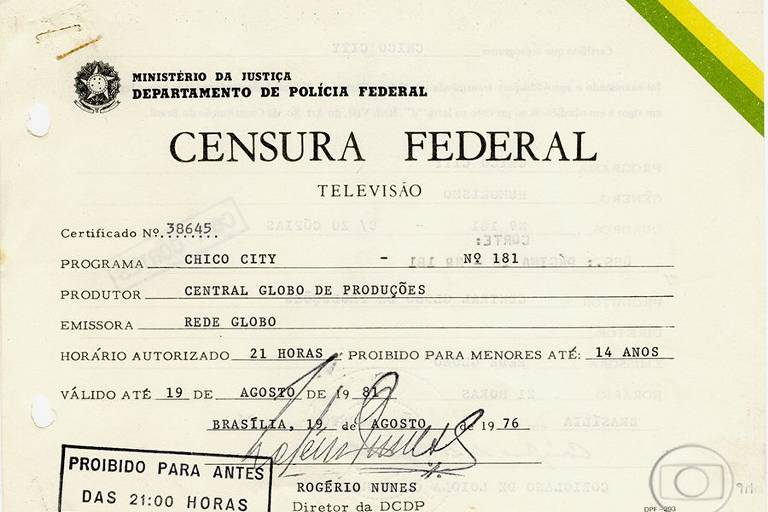

Censorship was part of the surveillance and repression machine set up by the military. Demonstrations that displeased the regime were forbidden in the newspapers and the arts or even in classrooms.

In a survey of the book "1968 - The Year that Has Not Ended," journalist Zuenir Ventura points out that, between 1968 and the end of 1978, when AI-5 was in effect, which intensified the repression, the government censored 500 films, 450 plays, 200 books, 100 magazines, and more than 500 lyrics.

Anyone who dared to express ideas that sounded inconvenient, in addition to having a text or work banned, ran the risk of responding to Military Police Investigations (IPM), the IPMs. This meant they had to give statements that included the threat of imprisonment, torture, and murder. It was "cultural terrorism."

In press censorship, the publication of "Os Lusíadas," a Portuguese epic, became famous, replacing forbidden news in "O Estado de S. Paulo." Between August 1973 and January 1975, verses by Camões appeared 655 times on pages banned by censors, installed inside the newsroom.

In 1974, the headline "Os Lusíadas - Canto Primeiro" replaced the news that Governor Laudo Natel had prohibited the disclosure of cases of meningitis.

The outbreak had started on the outskirts of São Paulo. The federal government chose to face the crisis by denying it and demanded the same from the press.

In addition to prior censorship, there was severe punishment if anything breached the stipulated restriction.

One known episode is the arrest of Folha columnist Lourenço Diaferia in 1977. His "crime" was publishing a column in which he compared Duque de Caxias to a sergeant who had died while jumping into a pit of otters at the Brasilia zoo to save a boy.

"I say, with all my letters, I prefer this hero sergeant to Duque de Caxias," he wrote in the article, which the military considered provocative. Folha continued to publish the column space in white while he was in jail.

Because of this, the newspaper the government pressured the paper to dismiss managing director Cláudio Abramo, considered subversive. He remained connected to the newspaper, however, as a correspondent and columnist.

With several tentacles, the government also pushed censorship by helping to kill off publication, as happened with "Correio da Manhã." In his chronicles, journalist and writer Carlos Heitor Cony denounced wrongdoing on the first day of the new regime. The daily, which remained critical despite increasing pressure, lost public and private advertising due to the government's coercion. The directors and the owner, Niomar Moniz Sodré Bittencourt, were arrested, and a bomb was detonated in the newsroom. It closed in 1974.

A side effect, then, was self-censorship. The government facilitated the work by sending daily tickets with what was prohibited and how to report on specific issues.

On TV Globo, Dias Gomes, a playwright targeted by the regime, once wrote to Boni, the station's director, complaining that TV Station workers looked like censors: "When I pass by the doormen, I fear that one of them will call me and say: 'I saw that episode on the videotape. I think you must change that scene, that doesn't pass.'"

He authored "Roque Santeiro," a soap opera censored in 1975, on the eve of its premiere. Globo responded with an editorial on "Jornal Nacional," which, for the first time, showed a rift between the broadcaster and the dictatorship.

The government-controlled soap operas chapter by chapter and cut words, phrases, entire scenes and even changed the direction of characters, with the censors being true co-authors. They also timed kisses to say how many seconds should be cut and to accompany the edition, ordering changes to the directors.

To annihilate what was considered "of poor quality," censors put on a show of arbitrariness.

The presenter Chacrinha was issued an arrest warrant for questioning a censor who went to the studio to complain about the clothes of the program's dancers. He couldn't even take off his presenter clothes before he was taken to jail.

In journalism, TV stations also had to show strategic content for ideological war, such as testimonies of young people in the armed struggle who declared themselves "sorry" after being tortured.

Government officials took at least four straight from the barracks, with machine guns pointing at them, to Globo. On TV, Tupi, in front of authorities, Massafumi Yoshinaga, of the Popular Revolutionary Vanguard, praised the government and the "people's enthusiasm for the World Cup." When he was released, he went into depression and hung himself.

This was the "Onwards, Brazil" image that the dictatorship was trying to sell. Those who questioned it were censored, and those who praised it benefitted.

In an attempt to get closer to cultural production, the military regime launched the National Culture Policy, which favored sponsorship and created institutions such as the National Cinema Council and National Arts Foundation.

It also strengthened the already existing Brazilian Film Company and National Theater Service, in a game of good cop, bad cop with theater and cinema, taken by the opposition.

Due to censorship of plays and films made the eve of their premieres, the dictatorship made investing in these productions an adventure.

This was the case with the 1973 musical, "Calabar," by Chico Buarque and Ruy Guerra. On the eve of its premiere, the government banned it.

Chico had already been censored in his first play, "Roda Viva," in 1968. In addition to the veto, the provocative montage by Zé Celso, from Teatro Oficina, led extreme right groups to attack the cast and to plunder the sets.

The composer also had his music censored, and, feeling threatened, he went into exile. Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil, Geraldo Vandré, Nara Leão, and so many other artists also went into exile.

Composers used metaphors to circumvent censorship. They created double-meaning classics like "Apesar de você ("Despite you, tomorrow will be another day ..."), by Chico, "Cálice" ("Pai, get me away from this Cálice ...", a pun on "shut up"), by Chico and Gil, and "Aquele Abraço," in which Gil says goodbye to exile.

The expulsion from the country was also a way of quieting teachers and intellectuals, in addition to acting as a professional purge, as happened with Fernando Henrique Cardoso. After returning from exile, he was compulsorily retired from USP at the age of 37.

The government contemplated the censorship of books in a 1970 decree, but it was revoked after a harsh reaction from authors.

Despite this, works started to be banned any time after the coup and involved police raids, apprehensions, and coercion of writers and publishers.

Ênio Silveira, owner of Civilização Brasileira, a stronghold of works by communist intellectuals, was arrested seven times and had his publishing house burned.

Censorship is a weapon of dictatorships because dissent, after all, weakens tyrannies, as pointed out by journalist Eugênio Bucci. He is a professor at the School of Communications and Arts at USP, author of "Is there Democracy without Factual Truth?" (ed. Estação das Letras e Cores) and members of the research group Journalism, Law, and Freedom. He points out that it is obedience, not debate, that gives stability to authoritarian regimes.

"To remain in power, dictators need to control ideas and artistic manifestations. They cannot live with freedom. Every dictatorship needs to establish censorship. Every authoritarian regime is pure fear of change, fear of transformation, fear of freedom - fear crystallized in paranoid control over others' lives, and obsessive censorship against everything other than the boss's obedience and praise. Where censorship or censorship praise exists, there is a dictatorship, or at least a ruler, who wants to become a dictator."

Censorship survived in democratic periods in Brazil, so much so that the military used a 1946 decree as the basis, the year in which the country lived a democracy.

Even after the 1988 Constitution, culture did not completely get rid of the restriction. But democracy provides the checks and balances of institutions that, under the dictatorship, lived under the tutelage of the regime.

In the dictatorship, moreover, the State is usually confused with the values and wishes of the representatives and decides what can and cannot be seen in a unidirectional way, as underlined by USP historian Marcos Napolitano, author of "1964 - History of the Brazilian Military Regime" (ed. Contexto).

In a democracy, the beacons for freedom are not in the hands of the government.

"In the democratic state, if a person, a group, or an institution feels offended or threatened by cultural work or a publication in the newspapers, they have the right to go to court. In turn, the latter assesses whether the content defamed, slandered, manifested prejudice, intolerance, or incited crime and violence. There will be a process, witnesses, technical opinions, to support the decision on any veto or redress, which can still be questioned in several instances," says Napolitano.

Censorship acts can be denounced in democracy, while in the dictatorship, news about censorship also used to be prohibited.

Society was unaware that information or work had been misused. Readers called "Jornal da Tarde," complaining that the recipes were not working.

It should be noted that in the recipe at the beginning of this text, you should add the yeast only after beating the other ingredients. Whether it is good or not, the important thing is that the chocolate cake was not imposed by the dictatorship.