When looking for military dictatorship fingerprints in Brazilian public security, three fallacies emerge.

The first is the false impression that the regime was a period of control and efficiency, with low crime and without corruption among public officials. This motivates some nostalgia for some of the period.

The second is the misleading attribution of the origin of all the ills, violence, and incapacities of today's police to the years of military command.

The third is the illusion that the Amnesty Law and the Constitution of 88 would be enough to end violations of the dictatorship and lead the country's institutions to automatically adhere to the principles of the democratic rule of law.

The authoritarian regime did not invent torture, police violence, or extrajudicial executions. It did not inaugurate corruption, impunity, or repression of popular movements.

Although commanded by generals, it also did not institute the police's militarization, even though the period deepened this aspect.

This is because the first policemen emerged during the Brazil Empire as armed guards at the service of the elite slave owners. These forces later became militarized forces and, finally, small armies operated by local oligarchies.

The lack of unprecedented criminal practices perpetrated by the regime, however, does not mean the absence of a legacy from the dictatorial period for the security forces of a Brazil that was opening up to democracy and that today, 35 years later, is breaking records of police lethality, taking the lives of mostly young, black and poor Brazilians.

"The dictatorship did not invent evil, and the police here have never been an example of quality," said political scientist and professor at USP Leandro Piquet. "The dictatorship even helped to standardize the state forces, which became more uniform after 1964. But violence, torture, and racism have always been present in the institutions, which strive to improve their service."

By perfecting unofficial practices already known in history and making them State policy, the military regime seeded the police's operational culture and values with brutal and authoritarian methods legitimized by the commands.

"With the dictatorship, rights and guarantees were suspended as obstacles to the efficiency of the military apparatus in the war against subversion," said political scientist Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro, former Human Rights secretary of the FHC government and member of the National Truth Commission (CNV ) in the Dilma Rousseff government.

The dictatorship's repression and death machine, which included classes in modern torture techniques for civil and military police, was made possible thanks to the establishment of the 1968 AI-5 and the 1969 decree 667.

The former suspended constitutional rights and guarantees under the pretext of creating conditions to free the country from the supposed communist threat.

The second centralized the coordination of state military police - generally formed from the merger of civilian guards with militarized public forces - under the army's control and direct command of the generals.

"Torture, previously applied to common criminals, became widespread for any militant opposed to the government, like me," recalled sociologist Michel Misse. He illustrates the extent of this practice with data from his Social Sciences and History class at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, where he is now a full professor.

"Out of 100 students, 40 were arrested and tortured. And this was repeated in Chemistry, Physics, and Engineering. That is, it was not something so selective."

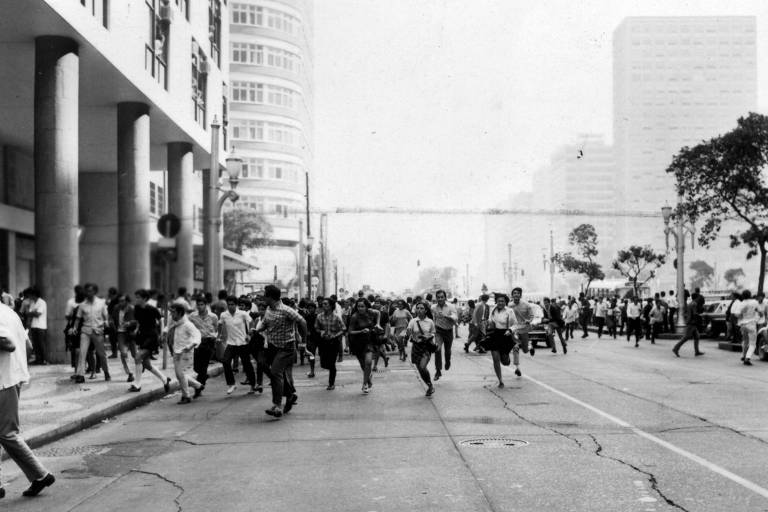

When confronting the guerrillas, defeated in the early 1970s, the police, faced with growing and increasingly violent urban crime, responded with the instruments consolidated in political repression.

"From 64 to 85, state military police academies began to teach guerrilla and counter-insurgency strategies and tactics. The disciplines of law and community policing only returned after 1985", recalled Glauco Carvalho, reserve colonel and former police commander in the capital of São Paulo.

"In the dictatorship, what is becoming stronger is a model of policing and an even more militarized organizational culture, inspired by what the Army was," said Samira Bueno, executive director of the Brazilian Forum on Public Security.

This process has in the notorious Rota, the Ostensive Rounds Tobias Aguiar, an exemplary case. Derived from the Army's Hunters Battalions and banking rounds, the Rota was created in São Paulo in 1970 for highly dangerous actions at a time of accelerated growth of the São Paulo population capital and the intensification of inequalities in the city.

"The peripheries increased, the dynamics of criminality changed, becoming more professional, and Rota started to get involved in these cases with total freedom to kill," says Samira.

It is now in the name of the war on crime that acting outside the law, hurting citizens' rights or killing are tolerated by parts of the police force as legitimate or even necessary strategies to act against suspects and criminals.

"The vulgar ideology of the good thug is a dead thug permeated part of the corporation. This minority ends up prevailing because nothing has been done about it", criticized Pinheiro.

It should not be a coincidence that the proliferation of so-called death squads in this period, the most famous of them called Escuderia LeCocq, in Rio de Janeiro, and identified with the symbol of a skull with red eyes.

"These groups are born to avenge the death of fellow police officers. Then they start to act preventively, doing justice with their own hands, and then they start offering extermination services, selling their homicidal skills," explains anthropologist Luiz Eduardo Soares.

"These sectors were auxiliary to official repression, working directly in the basements of the regime and deepening practices and values", said Soares, who was National Secretary of Public Security of the Lula government.

"There will be a social accumulation of a culture of arbitrariness, violence, and corruption within the police without this leading to warnings, consequences or punishments," highlighted Michel Misse, who sees as a consequence the invisibility of these problems in the eyes of the population, for whom these information does not arrive.

"The absence of a typical dictatorship investigation worked as a leaven for these practices, favored by the silence of the press, whether by censorship or by a combination of interests," he points out, exposing the cause of the first fallacy cited in this text about the military regime and security public.

The crimes committed by agents of the security forces were considered only by a proper, corporate and non-transparent Justice, favoring impunity.

By compiling health research data on violent deaths in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro during the dictatorship, researcher and lawyer Alberto Kopttike, director of Instituto Cidade Segura Kopttike, revealed results that dismantle the false image of control and efficiency against crime built by the civil-military regime.

According to him, the period between 1965 and 1985 actually marks the beginning of the violence epidemic in Brazil, with a massive explosion in the number of homicides and crimes against property. In São Paulo, for example, the murder rate grew 390% in those years. According to data from the São Paulo Public Security Secretariat, between 1999 and 2018, the rate fell by 83%.

Despite all this, the great testaments of the civil-military regime for the new Brazilian democracy are the Amnesty Law of 1979 and article 144 of the 1988 Constitution, which deals with public security and establishes a mere continuity of what was in the sector during the dictatorship.

"Matrix negationism was the transition to democracy, when, due to the correlation of forces, it was decided not to implement transitional justice, throwing corpses, ashes and official barbarism under the carpet," says Soares.

With extremely high levels of police violence, the Brazilian State fails to take the necessary measures to end impunity for extrajudicial executions, torture, cover-ups, and to break the cycle of violence that prevents the police from adequately protecting Brazilians," said Maria Laura Canineu, executive director of Human Rights Watch in Brazil.

Without blaming the actors of the regime or purging those responsible for the institutions' illegal practices, Kopttike pointed out that Brazil ended up contaminating the new democracy with the dictatorship's DNA.

Studies show that countries that have not carried out transitional justice processes are at greater risk of returning to live under dictatorships.