Invasions, land grabbing, deforestation, and illegal hunting are some of the current challenges faced by the Chico Mendes Extractive Reserve in the state of Acre, where the rate of forest loss has doubled since 2018. This worrying picture is reported by activist Ângela Mendes, executive chairperson of the Chico Mendes Committee. Ângela is also the eldest daughter of Chico Mendes, a well-known Brazilian environmental leader and rubber tapper murdered in 1988.

The situation is aggravated by the government's omission, says Ângela, in addition to the threats posed by bill of law PL 6024/2019, currently being read at the Chamber of Deputies [Brazil’s Lower House]. The bill, sponsored by Deputy Mara Rocha (PSDB-AC), proposes to reduce the area of the reserve (currently at nearly 1 million hectares, or approximately 1 million football fields).

"Local government has not responded, as it has a very close relationship with the agribusiness sector — which is precisely the sector behind the idea", says Ângela.

Another challenge for Ângela is how to help strengthen the identities of forest peoples and ensure that young people do not abandon their extractive reserves. "Our current education system creates a divide between young people and their culture", she says.

Brazil celebrates Amazon Day on 5 September. This year, Angela has been invited to address the European Parliament on the occasion. Her speech will focus on Europe's responsibility for forest conservation.

"Amazon exploitation results largely from market demands coming from Europe: demand for cattle, wood, and soy", she explains. "When Europeans consume these products, they need to do so in a conscious manner. Europe needs to ensure that it is not driving further violence and deforestation."

With regard to conflicts and murders in the region, such as her father's assassination years ago, and the recent murders of indigenist Bruno Pereira and journalist Dom Phillips, Ângela stresses the need for Brazil to improve its policies, protecting activists and promoting transparency in investigative processes.

"My father was murdered [in 1988], but much earlier Wilson Pinheiro was also killed [a rubber tapper leader from Acre, who died in 1980]. The recent murders of Bruno and Dom Phillips has brought to light many things that usually remain hidden."

The state of Acre and the Chico Mendes Extractive Reserve have both experienced high rates of deforestation in recent years. How has the government responded to this, and how does it affect people's lives? Today, the Chico Mendes Extractive Reserve is a highly threatened conservation unit. It suffers the most attacks in Brazil, and has the highest annual deforestation rates in the whole state of Acre. We are also opposing bill PL 6024, which aims to reduce the area of the reserve.

Local government has not responded, as it has a very close relationship with the agribusiness sector — which is precisely the sector behind the idea. Agribusiness interests are also behind most land invasions and land grabbing. This does not affect only the Chico Mendes Extractive Reserve — but that is where the presence of these groups seems to be stronger.

So, we have invaders coming from Rondônia, but also from other states, and who work alongside illegal hunters and criminal gangs; and this is aggravated by a lack of response from the public power.

Acre governor Gladson Cameli (PP) defends the expansion of agricultural production and the creation of a development zone covering the states of Amazonas, Acre, and Rondônia: Amacro. How do extractive communities view this project? Well, they have no proper opinion, nor do most people living in Acre, as this has not been openly discussed with anyone. It is being decided behind closed doors by state governments and their teams. The project affects the areas with the most conflicts: southern Amazonas is currently the stage for major agrarian conflicts, and so are the areas in Rondônia and Acre that would form this Amacro region.

We regret this lack of transparency. Their discourse claims to promote sustainable development for the region, but a type of development that reflects only the perspective of those who are in government today. There have never been public consultations on this project.

You have repeatedly argued that a Standing Amazon plays a key role in any climate solution; but how can we ensure that forest protection also meets the needs of the Amazon population, and raise their socioeconomic status? What istricky here is the extremely predatory exploitation model that has been in place in the Amazon: the idea that the Amazon is just a source of raw materials, and that it only serves to meet market demands, whether for meat, soy, or wood. But [we must remember that] the populations that live in the Amazon are also the key for any solution.

The UN has already acknowledged that Indigenous peoples and their territories protect the forest. And we have other groups of people that also act as guardians of their lands, building on their traditions, knowledge, and practices. But we should not aim for large-scale production of this, that, and the other: we're talking about preserving identities.

For example, the Chico Mendes Extractive Reserve has a total area of 1 million hectares. All of it would have been deforested had it not been for the extractive reserve, which, despite its problems, plays this important role of keeping almost 1 million hectares of standing forest.

Could you give us some examples of these alternative solutions? Here in Acre, for example, we have Cooperacre, which is a union of small co-operatives whose members live in the extractive reserve. Cooperacre absorbs their production of rubber, Brazil nuts, açaí, and everything else that is produced in the forest.

We also have initiatives focused on our artisans. There are people who live in the forest and make beautiful things from what they gather in the forest. There is so much happening in the Amazon that nobody sees. Whenever we hear about the Amazon, it is always about deforestation — or when someone claims that the Amazon is an obstacle to development.

What have you done recently to strengthen this agenda at the Chico Mendes Committee? What are your priorities? The committee was created with the mission of protecting my father's legacy, recognising the important role that extractive reserves play in addressing the current climate crisis. My father had a vision far ahead of his time. An example of this is when he spoke about [the role of] youth.

We have been much inspired by his Letter to the Youth of the Future. We can understand the current strategic role played by youth for the preservation of forest peoples' territories, identities, and cultures, especially with regard to extractive communities that rely on Brazil nuts and rubber for their subsistence. Since 2016, we have strengthened the voice of these young people, especially those living at the Chico Mendes Extractive Reserve.

How to reconcile young people's demand for more education (which often means moving to a big city) with maintaining this bond with their territories and their rubber trees? How do you address this issue? Our current education system creates a divide between young people and their culture", she says. But this makes no sense, does it? In this regard, we have been discussing alternatives with the Federal Institute of Acre (IFAC) and the Federal University of Acre (UFAC); the idea is to propose a new teaching and learning approach for forest communities.

The committee is part of the Amazônia de Pé [Standing Amazon] campaign. What are the campaign's main proposals? Amazônia de Pé seeks to protect public lands in the Amazon, promoting Indigenous land demarcation, creating extractive reserves and other conservation units, and treating these populations more fairly. The idea is to protect the lands, but also the people living there, so that they actually make social use of the land, as established in our Land Statute.

We believe that this would greatly reduce conflicts over land. But creating [protected areas] is not enough: we must also have the right tools to consolidate these territories and implement public policies to guarantee and protect the lives of those people living there.

The Chico Mendes Extractive Reserve unfortunately provides examples of many things that should not be happening. It's so big, so vast! And the ICMBio [Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation] lacks the proper structure to handle it. These areas need public policies, including for education, health, or valuing forest production chains, so that we may consolidate this model.

You are currently travelling in Europe. Does your agenda have any link with the murders of Bruno Pereira and Dom Phillips? What role may the international community play in fighting violence in the Amazon? Yes, we cannot ignore such an important issue. My father was murdered [in 1988], but much earlier Wilson Pinheiro was also killed [a rubber tapper leader from Acre, who died in 1980]. The recent murder of Bruno and Dom Phillips has brought to light many things that usually remain hidden.

Today we have, for example, the Escazú Agreement, which guarantees transparency in all processes and encourages the local population to participate in investigations, as in the case involving Dom’s and Bruno’s disappearance.

If Brazil had done its homework, we would have been able to follow up things in a clearer and more transparent way — but we know that it did not go like that. Nobody had access to accurate and clear information. So, these instruments need to be further consolidated and enforced.

Brazil has a task ahead, and we need it to be fulfilled — both to ratify and operationalise this agreement, and also to enact it as a law. We need to improve and update our national programme to protect human rights defenders, social communicators, and activists.

Will this be the focus of your speech before the European Parliament on Amazon Day? Not just this one. We will also be addressing the fact that Amazon exploitation results largely from market demands coming from Europe: demand for cattle, wood, and soy. We need to find a way to control this demand, so that we may be certain that, even if we continue serving this market, we will not be inducing conflict in the Amazon.

When Europeans consume these products, they need to do so in a conscious manner. Europe needs to ensure that it is not driving further violence and deforestation.

What would you say is Chico Mendes's main legacy? Oh, he left us so much — he was amazing! His idea of collectivity is very modern, and the Forest Peoples Alliance [a project developed in the 1980s] built on this collective approach. Extractive reserves also resulted from this feeling of collectivity and caring.

I believe that his most beautiful legacy was not actually the concrete idea of [protected] territories, but rather the notion that when we do things together — collectively — we become stronger. Individualism is actually responsible for much of what we are experiencing today.

PROFILE

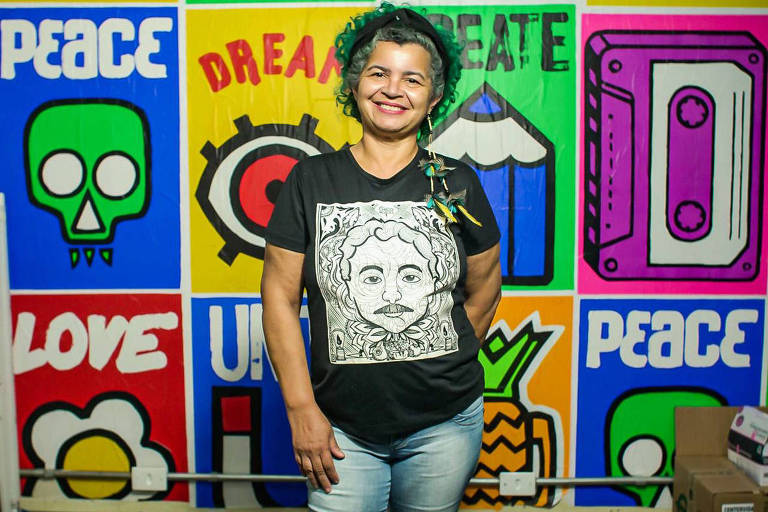

Ângela Mendes, 52

Ângela Mendes, the eldest daughter of Chico Mendes, Brazil’s famous rubber tapper leader and trade unionist, was born near the Cachoeira rubber groves in the municipality of Xapuri (AC). She has a specialised technical degree in Environmental Management, and is currently the executive chairperson of the Chico Mendes Committee. As a socioenvironmental activist, she joined Chief Raoni and politician Sônia Guajajara (PSOL) to create, in January 2020, an alliance against public policies issued by the Jair Bolsonaro government affecting environmental and Indigenous areas.

ABOUT THIS SERIES

Planeta em Transe (Entranced Planet ) is a series of reports and interviews with new players and experts on climate change in Brazil and around the world. This special coverage will also focus on the responses to the climate crisis during the 2022 general elections in Brazil and at COP27 (UN Climate Conference to take place in Egypt in November 2022). This project is supported by the Open Society Foundations