[Summary] Amanda Feilding, 76, has argued for over half a century that psychedelic compounds may help save humanity from ego-imposed neurosis. She has faith in science and believes the prohibitionist era is over, but she is in a hurry. To advance faster, she enlisted a Brazilian team in her lysergic crusade.

*

Room 224 at Princess Grace Hospital in London looks like an office. There are folders and boxes of paper lying on the floor of the lively talking patient Amanda Feilding, 76. You wouldn't have been able to tell that the Countess of Wemyss and March — a title acquired in 1995 by marrying James Charteris, Lord Neidpath, under an Egyptian pyramid — was currently hospitalized, apart from her bandaged right arm.

The hospital visit turned out to be the only opportunity for a lengthy conversation, as it had been scheduled for months. The interview would coincide with the psychedelic Breaking Convention conference. Amanda, however, fell ill and had to be hospitalized - which did not prevent her from escaping a day earlier to give one of the event's most popular lectures on LSD microdosing.

The plan that Friday, August 16, was to record the interview in a conference room at the University of Greenwich, where the conference was being held, as Amanda was due to travel to her Jamaican home on Sunday (which did not happen).

But she cancelled due to work. In this case she had a meeting with Brazilian neuroscientist Stevens Rehen through lunch and for most of the afternoon, to discuss the scientific collaboration that she today describes as her favourite.

Months earlier, she had had an accident while working in her London apartment at dawn. She suffered multiple fractures in her back, in the sacrum and iliac bones, which were only found weeks later. She also injured her arm, but she ignored it until her elbow began to swell.

An attempt to drain the fluid broke her skin and gave rise to an infection that antibiotics could not stop. When there was a risk of sepsis, hospitalization became inescapable. “It's all about being a workaholic,” she said while laughing.

So much dedication goes into the Beckley Foundation, which she founded in 1998 with the dual purpose of restoring LSD's prestige as a medicine, something that had been lost in the 1970s when lysergic acid was banned, and promoting drug policy reform around the world.

Amanda first took LSD in 1965, when it was still legal, and was soon convinced of the potential value of psychedelics. LSD went on to become her favourite: "I saw how it can go deep into the soul". Her interest in altered states of consciousness however, had begun much earlier.

Beckley, the foundation's name, comes from her family home an hour from London. A beautiful, secluded, three-moated Tudor hunting lodge. “My parents had the house, but no money. We lived there without central heating, but it was a fun life. I turned into my own world. My interests were Buddhism, mysticism, that sort of thing”, recalls the Countess.

Amanda attended the village school and then a nun’s boarding school, which denied her access to library works on Buddhism. At the age of 16, she decided to travel to Sri Lanka, with only 25 pounds in her purse, to find her godfather who had become a Buddhist monk. She, however, was held back by adventures in the deserts of Egypt and Syria living with Bedouin tribesmen and Dervish dancers, and did not make it to Sri Lanka.

Upon returning to the United Kingdom, she devoted herself to studying comparative religions at Oxford. Her tutor at All Souls was Professor Robert Charles Zaehner, who had written the book "Mysticism, Sacred and Profane."

The professor had experimented with mescaline, a compound extracted from the Peyote cactus that opened for Aldous Huxley "The Doors of Perception." Zaehner, however, had concluded that the psychedelic experience was different from the mystical ecstasy achieved with dance, mantra, meditation, or fasting. “Then, when I took LSD, I realized it really did create a mystical experience, very similar to that of mystics,” says Amanda.

Shortly after her lysergic initiation, she met Dutch scientist Bart Huges. He proposed a new hypothesis of the physiological changes underlying altered states of consciousness, namely: through a constriction of the veins, which bring about an increase in the volume of blood in the brain capillaries, thus provide extra glucose and oxygen for billions more brain cells.

Huges hypothesised that this change in cerebral circulation results in the ego mechanism relaxing its repressive grip, and thereby allowing the blood to be redistributed from the ego centres (or default mode network, as it is now called) to the rest of the brain, thus expanding consciousness.

Amanda fell in love with the idea, which still makes her eyes shine, and led her, a few years later, to undertake a trepanation. She drilled a hole in her skull to restore the natural pulsation of the arteries of the brain, resulting in a small increase in capillary volume. She launched her mind into the study of psychology, physiology and neuroscience, but in the style of the 1960s.

“I started to experiment. We lived on LSD before it was illegal, studying different aspects of humanity. What makes human beings what we are, brilliant and at the same time, in a way, a disaster, with this neurosis and psychosis that underlies humanity” she says.

“My passion had become to study the ‘ego’, its underlying mechanisms, how it controls us. With psychedelics, one can get to the root of the trauma. I spent three years psychoanalyzing myself, reading Freud and other authors, being a doctor and a patient at the same time”.

Today it is known that behind the action of LSD is its affinity for the receptor, 5-HT2A, specific for the neurotransmitter serotonin, which is important in mood regulation and is also a vasoconstrictor. Although LSD is associated with visual manifestations, the therapeutic potential is now under investigation. The compound discovered in 1943 by Swiss Chemist Albert Hofmann facilitates access to emotions, thoughts and memories — including trauma — usually unavailable to consciousness.

“We had to learn this unnatural behaviour so that the monkey could hunt in groups and do all these things unnatural for a monkey. This self-control (developed with the ego) has allowed us to get to the moon and do all the clever things we do, but it also brings the curse that makes us a neurotic animal” Amanda explains in her own way. "Our sense of reality is largely due to our conditioning”.

For her, the conditioning of the ego mechanism, which behaves like a government to its countrymen, creates a cloud, a veil, between humans and reality. That makes us a dangerous animal: “We are unpredictable, we can be brilliant, but also a threat to ourselves and the rest of the planet”.

Anyone who has taken LSD recognizes the experience of relaxation from the inner repression, currently described as ‘ego dissolution’. LSD became so popular with young people in the 1960s counterculture movement, that it motivated conservative reaction in the following decades, when the substance ended up banned around the world.

The ban also exterminated scientific experimentation with lysergic acid, which had shown such promising results in the treatment of alcohol addiction. Amanda reports how she got rid of her own nicotine addiction after becoming addicted at age 13:

“I decided to stop smoking on an LSD trip in 1966, and I never smoked another cigarette. This made me see how LSD could be used to strengthen one's own intention in the overcoming of the rigid thinking and maladaptive behaviour patterns that underlie such psychological illness as depression and addiction”.

The countess says she saw the ban coming as "a serious mistake" because it prevented the West from learning to use psychedelics intelligently, to their full potential, as traditional people do. So Amanda decided that the only way forward was to do the best science and explore how these compounds work in the brain and can be of benefit to humanity.

By the early 1980s, however, psychedelic research had become completely taboo, just as the term "consciousness" had become a dirty word in the scientific world. Amanda says Francis Crick, co- discoverer with James Watson of the molecular structure of DNA, had recommended never to mention the term "consciousness" in a grant application, or it would be refused.

In 1998, Amanda decided to create an institution, the Beckley Foundation, to pursue what she considers her mission in life. She also promised Albert Hofmann to rehabilitate his “problem child” (a title the Swiss chemist chose for his autobiographical book on LSD).

Because it was almost impossible to do science with psychedelics in the 1990s, as researchers could lose grants and jobs, Amanda saw the foundation as a Trojan horse: to change global drug policies and open the doors to psychedelic research. “Prohibition was a catastrophe, a cancer in the world, destabilizing countries, causing deaths, terrible violence, corruption, public health problems and loss of human rights.”

Her particular interest was psychedelics and cannabis, mistakenly placed in the same category as heroin, methamphetamine, and cocaine, all under one evil label, "drugs." Psychedelics are non-toxic compounds and incapable of causing addiction, and therefore should be removed from this category.

Amanda through the Beckley Foundation organised a series of globally influential seminars inviting high level politicians and personalities. These seminars were vital in forming a review movement for a scientific-base for drug policies, that would culminate in the Beckley Foundation Global Initiative Drug Policy.

Amanda says she believes that now in the field of science, too, a tipping point has been reached. It began discreetly in the 1990s with the advent of brain imaging techniques such as positron emission tomography (PET) and then functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

“These are new, amazing tools. I grew up as an artist, as a painter, and I saw that these images could provide a correlate for what was going on in the brain, for the subjective experience” she recalls. “But to get access to brain imaging, I needed to collaborate with researchers.”

She already had, on Beckley's board, renowned neuroscientists such as Colin Blakemore and David Nutt. With Blakemore in the late 90s, she sought to open a psychedelic study centre at the University of Oxford, but needed £4 million which Beckley could not raise.

In 2005, she approached David Nutt, a drug addiction specialist, and suggested that they collaborate on studies with psychedelics at the University of Bristol. Three years later, they set up the Beckley / Imperial College Research Program, which over the next 11 years yielded remarkable ground-breaking research. After finishing his PhD, Robin Carhart-Harris was employed as their first lead investigator.

The highly successful collaboration included a series of brain imaging studies conducted on individuals under the influence of psychedelics such as LSD, psilocybin, MDMA and DMT. Published results helped establish the idea that these compounds act by disabling the so-called default mode network (DMN), a communication circuit between specific neural regions associated with introspection, which becomes hyperactive and dysfunctional in various mental conditions such as depression, addiction and PTSD.

The Beckley/Imperial Programme conducted the first study to use psilocybin to treat patients with chronic depression, resistant to available treatments, such as SSRIs. It was published in 2016.

This study achieved encouraging results: 8 out of 12 patients achieved complete remission after one week, and 7 continued to meet criteria for response at 3 months, with 5 still in complete remission. But the test took place without a control group, in which some participants receive a placebo, due to the unique and obvious effects of psychedelics which a placebo cannot possibly mimic.

The first study to compare psychedelics and placebo to treat depression was conducted by a Brazilian group centered at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN). Researchers at the UFRN Brain Institute published in 2018 a study of 29 depressed patients, 14 treated with ayahuasca (tea containing the psychedelic DMT) and 15 with placebo. In the first group, 9 showed improvement; in the second, only 4.

The lead researcher was Dráulio Araújo, with Luís Fernando Tófoli, from Unicamp as one of the co-authors. Araújo is collaborating in other psychedelic studies with Sidarta Ribeiro from the same UFRN institute, and Stevens Rehen, from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and the D'Or Institute for Research and Teaching (Idor). They are now working with Amanda at the Beckley Foundation as part of the Beckley/Brazil Research Programme which has a pioneering programme of studies under way.

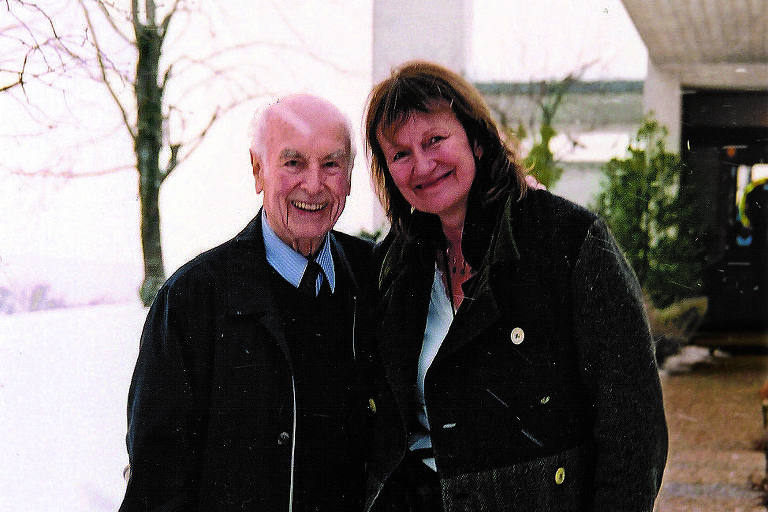

“Today my favourite collaboration is with the Brazilian group. I knew Sidarta well, and obviously I needed to work with a neuroscientist named Sidarta,” jokes the woman who discovered altered states of consciousness through the Buddhist religion.

Together they are looking to investigate how LSD affects the creation of neurons (neurogenesis and neuroplasticity), so learning and cognitive enhancement. “With the Brazilians we will expand this with Steven’s mini brains, Siddhartha’s rats, and finally with humans. It's a brilliant team to work with: open, energetic, wonderful, and exciting.”

Such studies will “incredibly” deepen our understanding, the Countess hopes, of how these compounds, especially LSD, can be valuable in other areas. In particular, neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia, Alzheimer's and Parkinson's.

The Brazilian group is based on Beckley's research plan, preclinical studies, but the foundation has two other arms in the program.

One is microdosing, the continued use of LSD in smaller quantities, a fashion that spread across Silicon Valley and of which Amanda has been a pioneer since the1960s. This is a collaboration with the University of Maastricht.

“I've always called LSD a ‘psychovitamin’, because it expands how you feel, improves your mood. You think better, become more focused, more interested in your own thoughts, relationships become more interesting because of the various points of view,” she argues.

She is interested in studying microdoses in various fields: creativity, pain, cognitive rescue of people slipping into dementia. "We are seeing that the creation of dendrites, axons and synapses increases, we may be able to reverse the advent of old age".

The other arm, clinical studies of LSD-assisted psychotherapy, targets new ways of treating opioid and alcohol dependence, as well as depression and anxiety in terminally ill patients. Amanda has set up partnerships with universities and institutes in various countries, from the Netherlands, Spain, USA and the UK to Australia, New Zealand, Russia and Switzerland. Besides Brazil, of course.

To accomplish all her research plans, she estimates that Beckley would need £ 1.5 million to £ 2 million a year, “crumbs for rich people.” Just to pay salaries and keep studies going, it's £400,000 a year.

“When insanity sets in, such as prohibition, it takes a long time to be undone. Luckily, I think we are now in a better period, slowly overcoming that. I hope it doesn't take another 50 years. I want to do a lot of great research over the next five years.”

Now, science and religion are reunited in the “mystical experience”, which is at the core of the healing process in psychedelic-assisted therapy. We lost religion and we gained science, she says. What is wrong with humanity, she believes, lies in our brains. Something is poorly organized there.

How do you improve the situation? "Maybe with the help of these gifts, the fruits of the gods.”